The core feature of a browser is HTML rendering. You can have a piece of software that can resolve domains to IP addresses or perform TCP 3-way handshake, but without images or colourful buttons, for the average users, it is not a browser! That’s why text-based protocols like the Gopher protocol are being disfavored and overpowered by the HTTP protocol that we have known as “the web” today.

One of the main building blocks of the HTML rendering process is the DOM API. Before a browser can render the HTML document, it needs to parse the document content into a tree structure called the DOM tree. In this post, I’ll break down my experimentation in building a DOM API with Rust.

Before we begin

Since this post contains considerable numbers of computer science and rust-related terms/concepts, I recommend that you acquire some knowledge on graph theory, Rust’s reference counted smart pointer and memory allocation before continuing. Otherwise, I hope God bless you.

What is a DOM tree?

DOM or Document Object Model is an API uses by the browser to represent and manipulate HTML documents. Usually, to represent a document, the DOM API creates a tree data structure with HTML tags as tree nodes, hence the name DOM tree.

DOM…tree, really?

If you have a CS background, you must be a big fan of the game . However, in this case, if you pay money and attention for an education in computer science (or you are a self-taught like me), you will know that in graph theory, there are two types of data structures-tree and graph.

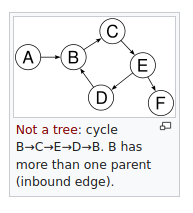

Since tags in an HTML document has a parent-child relationship, it’s best to represent the document using a tree structure…right? Yes, but if you think about it, each node of the tree can have pointers that point back to the parent, next siblings, previous siblings, etc. Those connections can and will create a loop in the DOM tree, which is very confusing since the tree, by definition, cannot contain a cycle.

But, while the idea of having pointers to other nodes in the tree seems to break the very definition of it, the DOM tree is still, technically, a tree. Sure it is full of connections and looks more like a graph than a tree. But the fact that each node only has 1 parent is what makes the DOM tree…a tree. After all, those connections are just pointers. They don’t own the data that they point to; thus, it is safe to say that a DOM tree is a tree.

Choosing DOM tree data structure

Because the DOM specs only specify the DOM API using interfaces (WebIDL),

the underlying implementation of the DOM is up to you to decide. That’s why

different browser engines have different implementations of the DOM tree. For

example, Gecko store DOM both as an array and a linked list so that

nextSibling/previousSibling or childnodes[i] operation take O(1)

complexity. On the other hand, Webkit only used a linked list to store the

DOM, which result in an O(n) complexity for childnodes[i] operation but with

a trade-off that it use less memory than Gecko.source

The browser that I’m working on is called Moon (yes, my originality is at its best). With this browser, I have chosen to store the DOM only as a linked list for memory efficiency.

DOM in Rust

Rust is a safety-first language, which means it doesn’t care about your feeling or your expertise in making a mess with JavaScript. If you violate the rules, it screams in your face.

Smart pointer

Despite Rust behaving like a grumpy old man, good things did come out of that. One of them is the prevention of dangling pointers.

A dangling pointer is a pointer that points to an invalid memory location. If you failed your pointer exam in college, think of it like “Doraemon’s Anywhere Door” or “The Magic Door” in Howl’s moving castle or for astrophysicists, imagine a wormhole that leads to a place that you didn’t expect it to lead to.

To solve that problem, Rust introduced smart pointers, which is a type of pointer that keep track of the memory that it is pointing to. For example, if a pointer is pointing to a vector and the vector’s length exceeds its capacity, the vector will be reallocated by Rust to a new location on the heap. This makes the pointer to become a dangling pointer since it doesn’t automatically update to the new location that the array was moved to.

A smart pointer, on the other hand, keeps track of the location of the data assigned to it. Therefore, it’s safe to operate on it without worrying about accessing invalid memory space.

Reference Counted Smart Pointer

Most of the time, you will only use smart pointers to point to data that stores on the heap. In those cases, the data’ ownership is determined, and it will be automatically freed/dropped/disappeared when nobody needs it anymore, kinda like…you…and me

But, in some cases, data ownership should be shared. For example, in a graph, a

node can be owned by many other nodes that point to it, which breaks the “no

sharing” rules in Rust. To enable such scenarios to happen, Rust created a type

of smart pointer, named Rc or Reference Counted Smart Pointer.

Rust book does a way better in explaning the Rc smart pointer than me:

Imagine

Rc<T>as a TV in a family room. When one person enters to watch TV, they turn it on. Others can come into the room and watch the TV. When the last person leaves the room, they turn off the TV because it’s no longer being used.

Since our DOM tree can contains nodes that are being pointed to by other nodes,

an Rc<T> is a perfect kind of pointer for this job.

Cyclic data and memory leaks

While Rc<T> can help us solve the shared ownership pointer problem, it also

introduces a new challenge called cyclic data.

When using Rc pointer, Rust performs garbage collection based on reference

counting, which means the Rc pointer holds a variable that keeps track of the

number of references to it. When the count decreases to 0, Rust will free the

data behind that pointer. Having cycles in your data is essentially not a bad

thing, but it requires good memory management. Otherwise,

reference cycles can easily lead to memory leaks with reference count garbage collection.

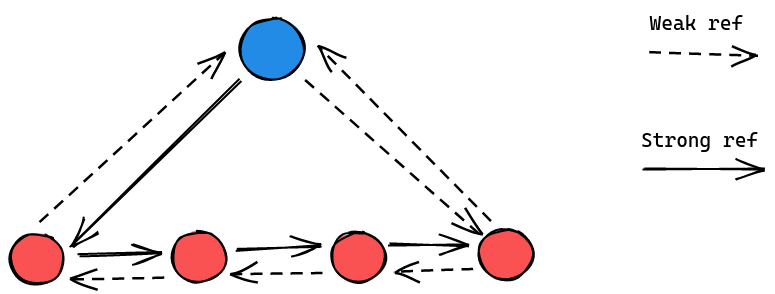

To cope with that problem, Rust introduces Weak references. Instead of

increasing the counter variable of the Rc pointer, weak references do not count

toward ownership of the data until upgraded into an Rc. Roughly speaking, when

you hold a weak reference to a piece of data, you only have a connection to it,

and the data may already be freed the moment you upgrade to an Rc pointer,

which in that case the upgrade will result in None value.

Rust book has a good chapter explaining how reference cycles can create memory leaks and how to tackle them using weak reference.

Solving the cyclic data problem

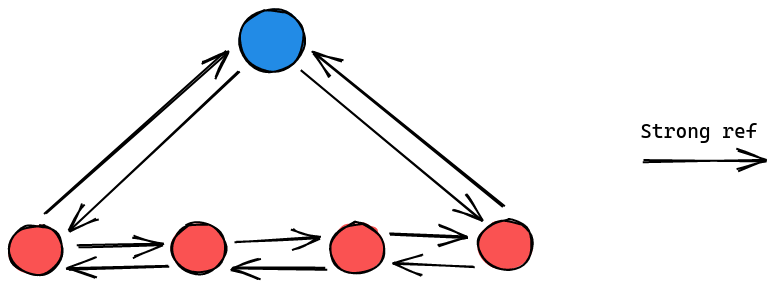

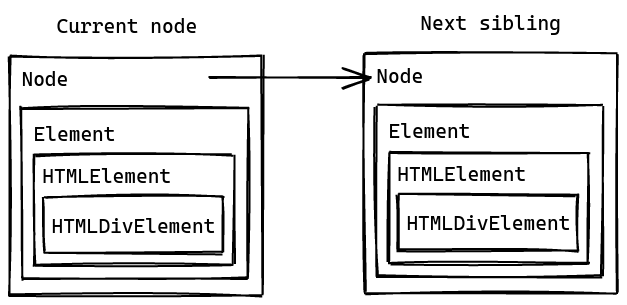

In a DOM tree, a node has connections to many other nodes across the tree. But in this case, we will only pay attention to its first child, last child, next sibling, previous sibling pointer.

If you look carefully, you can see that there are loops inside the tree above. Therefore, the current structure can create unwanted memory leaks. To solve this problem, we introduce weak references so that we can both solve the memory leaks problem while retaining the current DOM structure.

Of course, this is not the only way to solve this problem. Simon Sapin, who

works on the Mozilla Servo engine, has created an interesting experiment to

try out different methods to structure a DOM tree. His experiement includes

structuring the data in an arena so that we can assign an id for each node and

manage the node references ourselves or using Rc to structure the tree just

like what you read above. And in this case, I have decided to go with the Rc

tree approach for Moon.

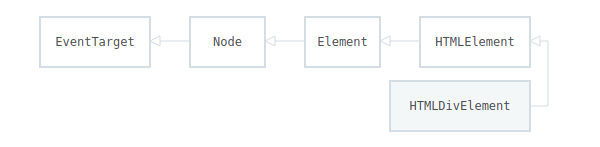

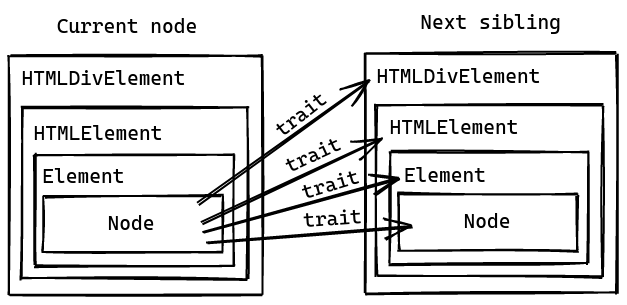

DOM node inheritance

While it is easy to perform inheritance in OOP languages such as C/C++, Rust doesn’t have an option for struct inheritance. The behaviours of a struct in Rust are shared and combined via “traits”, which makes it rely more on composition than inheritance.

This creates a new problem in our DOM tree structure since DOM API relies a lot

on inheritance. For example, this is the inheritance hierarchy for a simple HTML

div element:

Retrieve from

MDN

Retrieve from

MDN

Solving DOM inheritance

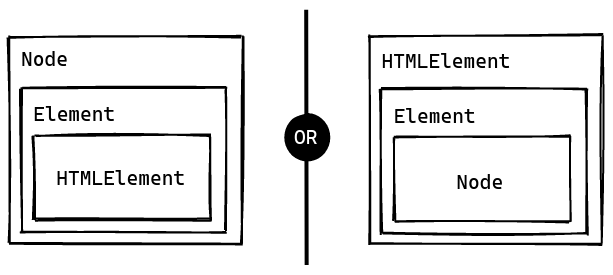

Since there’s no way to perform inheritance, the best thing to do as of right now is to store the structs in a nested manner. But the question here is: in which order?

Node -> Element -> HtmlElement

The first approach is to store the nodes in the order of their inheritance

hierarchy. With this approach, the Node type is the parent of all subtype,

which reduces the needs for node casting but also comes with some significant

downsides.

Because nodes are connected from the Node level, there’s no need for node

casting. If, for example, you want to obtains HTML data from a Node, you only

need to travel down from Node to Element to HTMLElement and so on.

The drawback here is you won’t be able to separate your structs. Technically

speaking, HTMLElement structs are not part of the DOM API, and you should be

able to separate them from it. However, in this case, if you move your

HTMLElement structs to a separate crate, you won’t be able to use the DOM API

in those structs because it will create circular module issue.

Another downside to this is the Node type can store not only Element but also

Document, Text, Comment, etc. Therefore, before performing any action on

it, you will have to check if it contains the right type of data for that

action.

HTMLElement -> Element -> Node

So how do you tackle the problems above? You do the complete opposite, of course .

Storing nodes in the opposite direction gives you a more modular and easy to separate structure since the inner node type doesn’t depend on the outer one.

However, as you can already guess, to associate those nodes together, Rust requires abstracting them using “trait object”. But when you can only access the objects via its trait, how can you access its inner data? That is when the ability to cast a trait object into a specific node type becomes indispensable.

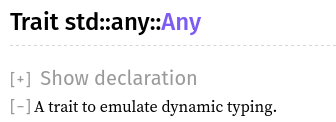

Enter Any trait!

Yes, Rust’s developers do think of everything. I won’t go into the details of

how the trait works because I don’t really know either it’s not relevant to

this post.

But the way this trait can solve our problem is by allowing us to transform a

node to an Any trait object, then proceed to cast it into any type that we

want.

trait DOMObject {

fn as_any(&self) -> &dyn Any;

}

impl DOMObject for Element {

fn as_any(&self) -> &dyn Any {

self

}

}

let node: Rc<RefCell<dyn DOMObject>> = Rc::new(RefCell::new(Element::new()));

// casting

let element: Element = node.borrow().as_any().downcast_ref::<Element>();With this solution, we are now able to create a node of any type with minimum dependence. Plus, we also have a very logical API design!

That’s it folk

That is all I can share about my journey to build the DOM API for my browser. If you survived this post, I hope that you have learnt something new today. If you haven’t, Moon is open-source on Github, don’t hesitate to stop by and study my mistakes closely .

https://github.com/ZeroX-DG/moon

Till next time!

Resources

- Wikipedia. (2020). Memory leak

- Rust Book. (2020). Reference Cycles Can Leak Memory.

- Jeff Walden. (2013). Is the DOM NodeList a linked list or an array?

- Simon Sapin. (2020). Rust forest experiement.

- WHATWG. (2020). DOM Living Standard.

- Rust Book. (2020). Rc<T>, the Reference Counted Smart Pointer

- Simon Johnston. (2020). xml_dom

- SerenityOS. (2020). SerenityOS DOM API