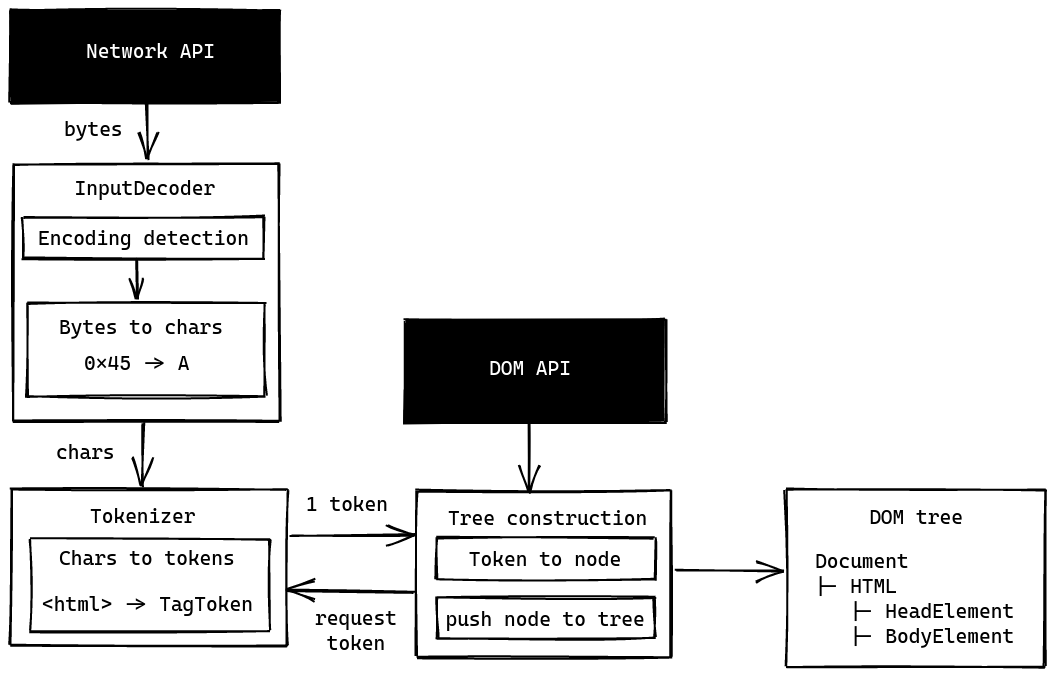

When a browser starts to render a page, it first transforms the HTML code into a DOM tree. This process includes two main activities:

- HTML tokenization: Transforming input text characters into HTML “tokens”.

- DOM tree building: Transforming HTML tokens from the previous step into a DOM tree.

Because there’re only two main activities, implementing an HTML parser should take you no more than 6 hours agonizing over the HTML5 specification, three weeks implementing half of the parsing algorithm and 2 hours questioning the meaning of existence…every single day. The implementer is then expected to experience several after-effects that may include: confusion, regret for not using Servo’s HTML parser, and Friedrich Nietzsche starts to sound fascinating:

To live is to suffer, to survive is to find some meaning in the suffering.

But since I have foolishly made a promise with the first three words in the name of this series, let’s build an HTML parser from scratch

Note: I will just going to give you an overview of how the parser works. If you are interested in the implementation, please refer to Moon’s parser source code and HTML5 specification.

The parsing flow

Input decoder

When the browser receives an HTML document from the server, everything is

transfered as raw bytes. Thus, to decode those bytes into readable text

characters, the browser will first run the encoding sniffing algorithm to

detect the document’s encoding. This includes trying out various methods from

BOM sniffing to meta detection.

BOM sniffing

BOM or Byte Order Mark, is like a magic number in files. When opening

a file in a hex editor like bless, if the file starts with 4A 46 49

46, we know that it’s a JPEG file; 25 50 44 46, it’s a PDF file. BOM

serves the same purpose but for text streams. Therefore, to determine the

encoding of the text stream, the browser will compare the first 3 bytes with the

table below:

| Byte order mark | Encoding |

|---|---|

0xEF 0xBB 0xBF | UTF-8 |

0xFE 0xFF | UTF-16BE |

0xFF 0xFE | UTF-16LE |

Meta detection

Back in 2012, when emmet is not yet a thing, and developers still typing HTML manually from start to finish, I often find myself missing a crucial tag that I have no idea how it works back then:

<meta charset="utf-8" />This result in my browser displaying Vietnamese characters as ”�” character, which for those who don’t know, is called “replacement character.” This issue was so popular back then that people started to paste replacement character into text inputs intentionally to troll webmasters and make them think that the database has a text encoding issue

Anyway, now you know that if the browser can’t find the BOM, it will try to

detect the document encoding via the meta tag. But you probably won’t have to

worry about this since HTML autocomplete is quite powerful these days, and they

usually generate that meta tag by default.

Tokenizer

Note: If you are not familiar with tokenization, be sure to read a bit about it here.

After the stream of bytes is decoded into a stream of characters, it’s then fed into an HTML tokenizer. The tokenizer is responsible for transforming input text characters into HTML tokens. There are fives types HTML tokens:

- DOCTYPE: Represent and contain information about the document doctype.

Yes, that useless

<!DOCTYPE html>isn’t as useless as you think. - Tag: Represent both start tag (e.g

<html>) and end tag (e.g</html>). - Comment: Represent a comment in the HTML document.

- Character: Represent a character that is not part of any other tokens.

- EOF: Represent the end of the HTML document.

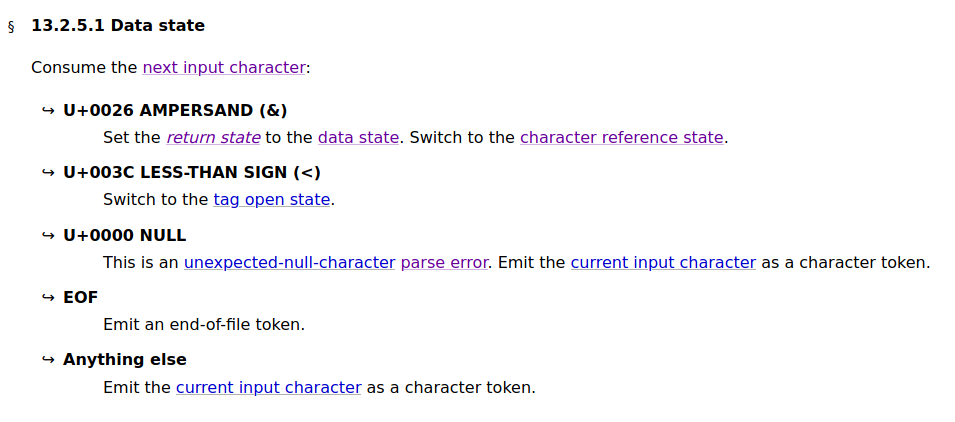

The HTML tokenizer is a state machine, which first starts at an initial

state called the Data state. From that, the tokenizer will process a character

according to the instruction of that state. The tokenization ends when it

encounters an EOF character in the text stream.

The instruction for data state tokenization

The instruction for data state tokenization

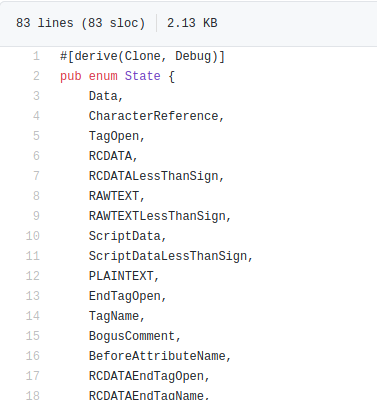

But don’t be fooled by the small number of tokens and think that this is easy to implement. What gives me PTSD after implementing the tokenizer is the sheer number of tokenizer states. 80, to be exact.

A small section of the states from

moon source code

A small section of the states from

moon source code

A complete list of states can be found here.

Tree-building

The way the tree-building stage works is similar to the tokenize stage. It also switches between different states to create the DOM tree. What special about this stage is it have a stack of open elements to keep track of the parent-child relationship, similar to the balance parentheses problem.

Therefore, to build the DOM tree, the tree-building state machine will process the tokens emitted by the tokenizer one by one. If it encounters any script tag, it will pause the current work and let the JS engine does its job. After that, the tree-building process will continue until the EOF token is received.

One thing to notice when implementing an HTML parser is the tree-building stage doesn’t happen after the tokenize stage. As stated in the specification:

When a token is emitted, it must immediately be handled by the tree construction stage. The tree construction stage can affect the state of the tokenization stage, and can insert additional characters into the stream.

Consider this piece of HTML code:

<p>this is a paragraph</p>

<script>

document.write("<p>this is a new one</p>");

</script>

<p>this is another paragraph</p>

<!-- very long html below... -->Because of document.write, the code starting from the end of the

</script> to the rest of the file will be cleared. Thus, if your parser

attempts to tokenize the whole file before performing tree construction, it will

end up wasting its time tokenizing redundant code.

Therefore, to tackle that problem, the browser has the ability to pause the HTML parsing process to execute the JS script first. Therefore, if the script modifies the page, the browser will resume parsing at a new location instead of where it left off before executing the script.

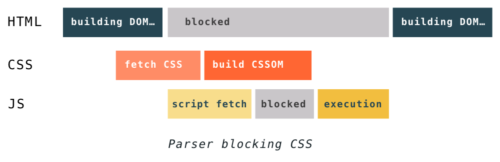

That’s why JavaScript will block rendering and should be placed at the bottom of the HTML. It also reveals why CSS is also render blocking. When JavaScript runs, it can request for access to the CSSOM, which depends on the CSS; thus, the CSS will block the execution of JS until all the CSS is loaded and the CSSOM is constructed.

How CSS block rendering. Source

How CSS block rendering. Source

Bonus

Here are some extra cool things that I learnt after implementing this HTML parser:

Speculative parsing

As I explained before, because JavaScript can potentially modify the page using

document.write, the browser will stop the HTML parsing process until the

script execution is completed. However, with the Firefox browser, since Firefox

4, speculative parsing has been supported. Speculative parsing allows the

browser to parse ahead for any resources it might need to load while the

JavaScript is being executed. Meaning, the browser can parse HTML faster if

JavaScript doesn’t modify the page. However, if it does, everything that the

browser parsed ahead is wasted.

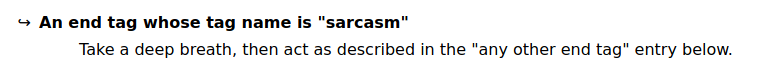

</sarcasm>

After hours of implementing dry HTML parsing rules, this one really makes me question my own sanity

<ruby>

At first, I thought this tag has something to do with the language Ruby. But turn out, it’s a tag to specify a small piece of on top of another text to show the pronunciation, otherwise known as ruby. For example:

河 內 東 京

<ruby>

河 內<rp>(</rp><rt>Hà Nội</rt><rp>)</rp>

</ruby>

<ruby>

東 京<rp>(</rp><rt>Tō kyō</rt><rp>)</rp>

</ruby>That’s all I can share on my journey implementing the HTML parser. It’s not satisfying to read, I know. But even though it’s complicated to implement the parser, summing up how it works turns out to be quite a simple task; hence, the abrupt ending . But I hope that I inspired you to use Servo’s HTML parser instead of implementing it from scratch like me . If you somehow deranged enough to do what I did, I wish you the best of luck.

Resources

- Wikipedia. (2020). Tokenization

- WHATWG. (2020). HTML Living Standard

- Servo Engine. (2020). Servo HTML parser

- SerenityOS. (2020). SerenityOS HTML parser

- Milica Mihajlija. (2017). Speculative parsing

- Ilya Grigorik. (2020). Render Blocking CSS