Oh hello, it’s been a while. Sorry for making you wait but, it’s exhausting to write about such a dry process as building a browser, in an entertaining way…when I’m extremely lazy

But fear not! For the past few months, I’ve carefully studied the teaching of the great sloths to improve my productivity. Thus, I’m pretty confident that the gap between my posts from now on would widen significantly, so you can spend more time with friends and family and not with a depressed code writer who throws his life away, building a browser that barely works

Anyway, enough of my rambling! Let us dive into the dry cold world of browser engineering once more.

When life gives the browser a DOM tree & a CSSOM tree, it makes a render tree.

Similar to how you were created by mixing your parents’ genes minus some

redundant details such as your father’s intelligence or your mother’s good look,

combining the DOM tree with the CSSOM tree while filtering out all the nodes

that aren’t visible on the page (such as nodes that are display: none) gives

you the render tree.

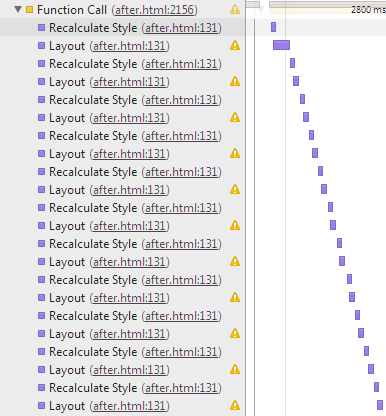

After constructing the render tree, the browser then computes the position of each DOM node in a process called “layout”. Being the most expensive operation in the browser rendering process, nothing wets developers’ pants faster than a long stack of purple layout function calls appearing in the devtool:

A view of layout thrashing from the chrome devtool

A view of layout thrashing from the chrome devtool

This phenomenon has the scientific name of “layout thrashing” but, a more

common title that circulates among div-centring engineers is: “Now who the f***

added a style update in my setInterval animation loop?”

You see, the layout process is scary not only because nobody knows what the f*** is going on in that black box, but also because it’s quite easy to trigger that process, which, if frequent enough, can make your FPS drop faster than your chemistry exam mark.

The reason for this is because to render a frame, the browser must perform a series of tasks that together is commonly known as a render pipeline:

A render pipeline

A render pipeline

Because the render pipeline executes its tasks sequentially, if the layout task takes too long to finish, it ends up blocking all the tasks that come after and could result in the render pipeline not completing within the frame’s time limit, thus, dropping the frame rate.

To put that into perspective. If your desired frame rate is 60 FPS, each frame

has roughly 1000ms / 60 ≈ 16.6ms to render. Meaning, within 16ms, the browser

has to execute every O(n!) JS function of yours, calculate all the styles from

your CSS and computes the position of every node in the render tree, before

painting those nodes onto million of pixels of your 4K screen. Now you

understand how the render pipeline feels, you barbaric monkeys.

Anyway, to calculate the DOM node’s position, the browser relies on a set of specifications that were written by very smart web developers. I didn’t mean to be sarcastic there. Seriously, hats off to those pioneers who literally defined the web we have today. They’re the reason why you’re reading this post and why I get paid at the end of the month.

Overall, the layout process consists of 4 main steps:

- Generating box tree/layout tree.

- Computing layout boxes positions.

- Computing layout boxes sizes.

- Repeat steps 2 to 4 for child boxes.

Box tree/Layout tree generation

Each node in the DOM tree generates one or multiple boxes to represent the rectangular areas that the node occupies on the page according to the box model. These boxes are linked together into a tree structure, which is called a box tree or layout tree.

There are two main types of box, namely, block-level box and inline-level box.

The block-level boxes are used for elements that take up the whole width of the

parent container (<p> is a good example). While inline-level boxes represent

elements that stack together horizontally to form a line. For example <span>

or <a>. The rules for generating these boxes are so clear that after reading,

you’d find yourself becoming “The Thinker”. Nude and confused about

everything.

But hey, if you want to see box generation works, feel free to dive into the specification.

Formatting context

When a box is generated, it establishes a formatting context to specify how its child boxes should be laid out. Different layout types have different formatting contexts, but the most popular would certainly be the flow layout with the Block Formatting Context (BFC) and the Inline Formatting Context (IFC).

In the BFC, boxes are stacked on top of each other. Thus, the BFC will only be established by a box if its children are block-level boxes. Similarly, boxes in IFC are stacked horizontally, and so every box must be an inline-level box.

But then what if there’s a mixture of inline-level & block-level boxes? What would the holy browser do to eradicate such heresy? Enter anonymous box.

Anonymous box

Let’s say if we have this HTML:

<div id="parent">

<span id="1">text</span>

<div>

<span id="2">text</span>

</div>

<span id="3">text</span>

<div>Since <div>s are display: block, they generates block-level boxes, and

<span>s on the other hand, generates inline-level boxes, the resulting layout

tree would look like:

[block-level (div#parent)]

|- [inline-level (span#1)]

|- [block-level (div)]

| |- [inline-level (span#2)]

|- [inline-level (span#3)]But rather than having a mixture of inline-level & block-level boxes, the browser always simplifies the structure by breaking it into anonymous wrappers, which are boxes that have no associated DOM node. This way, it ensures that boxes at the same nested level always share the same box type. Therefore, in this situation, the browser would break the above structure into:

[block-level (div#parent)]

|- [block-level anonymous]

| |- [inline-level (span#1)]

|- [block-level (div)]

| |- [inline-level (span#2)]

|- [block-level anonymous]

| |- [inline-level (span#3)]Compute box position & size

Once the layout tree has been constructed, the browser travels it to compute the

size and position of each box. The algorithm for calculating those properties

depends entirely on the layout algorithm. For example, in BFC, the width of each

box is the width that you explicitly specified using the CSS property width;

otherwise, the width of the parent box is used instead.

Having experienced death by boredom, I understand how unpleasant the experience can be, but if you enjoy the taste of tedium dripping on your tough while munching the CSS specification, here’s the link for ya.

The end

It’s been nearly a year since I started building this browser. I can’t say that I enjoyed the entire journey, but it certainly helped me in many ways. Maybe I’ll have a post about that, maybe I won’t, but in any case, I think this “Browser from Scratch” series should end here, and no, I’m not dropping this browser project. This journey has reached the point where writing about it is no longer enjoyable for me, and I’m pretty sure that it doesn’t make any sense for any of you if you never make a browser yourself. So from now on, I’ll only be writing about the discoveries that I made while developing this browser. Some might help you get a pay raise, some might not, but they will certainly be interesting to read, and hopefully, to write as well.

If you enjoy browser engineering & looking for more content, be sure to check out this curated list of browser engineering resources by me.

じゃあね

Resources

- W3C. 2020. CSS Visual formatting model

- W3C. 2020. CSS Visual formatting model details

- Ilya Grigorik. 2019. Render-tree Construction, Layout, and Paint